Don't create leftovers (DCL)

· 4 minutes readEverybody is familiar with the DRY principle in software engineering coined by Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas. It states do not repeat yourself in code to achieve less ambiguous code, avoid redundancy, and many other benefits in the long term.

In this post, I want to explain another pattern that I see over and over in all kind of projects and it brings problems and impacts the maintainability of your software project. It doesn’t affect the source code itself but the organization of the files that compose it.

What is a leftover?

In the lifespan of a software project, code gets created and destroyed to meet users’ expectations. During this period, it is easy to generate files, components, and other kinds of stuff that are not used any more. Those undesired pieces of software, make it harder to maintain, impact on your internal metrics, slow down your Continuous Integration check and other kinds of side effects.

Those leftovers from the past, don’t bring any value to the project and it can get to the point where nobody is brave enough to do a right cleanup to have a healthy codebase. This goes directly to the technical debt bucket.

Those items should have been removed when the last reference to them disappeared but a developer forgot to remove them. Those leftovers can be a unused image, a unused copy, a unused test on your test suite, etc.

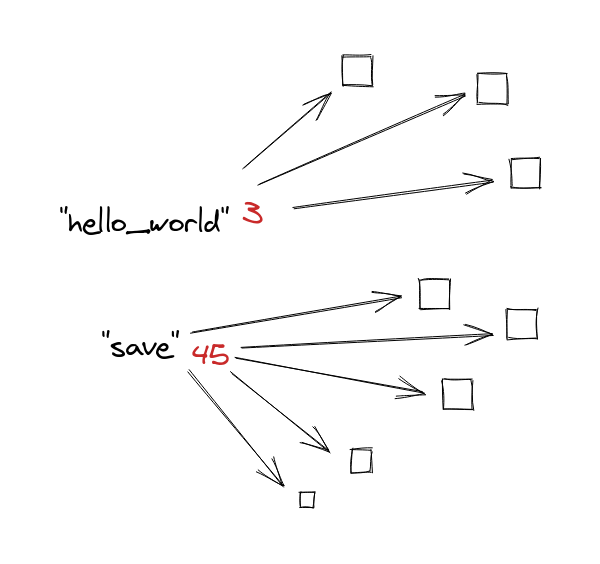

You can find many similarities and parallelisms with the responsibilities of a memory garbage collector. It keeps tracks the dependencies between parts, with a reference counting to be able to destroy all unused references. The problem here is that we don’t track this kind of information between the dependencies in our code base.

Why do we create leftovers?

This bad design pattern can have many shapes. This is another example where Don’t create leftovers impacts many projects today. How many of you have a translation system where translations live in one place and the place where they are used is in another one?

src/translations/en.json

{

"hello_world": "Hello World!"

}src/components/hello_world.jsx

export default function HelloWorld () {

return (

<div>{i18n.t('hello_world')}</div>

)

}The problem with this translation approach is that if the HelloWorld

component disappears in the future, the copy in en.json will be forgotten unless

a developer remembers to clean it up. At some point in the future, your

main translation file starts to have hundreds of unused keys that make you lose

money with each new language you want to support.

Some translation systems are aware of this and follow a much better approach. They have an extraction step to retrieve all translations from the codebase. With this, the list of used copies (dependencies) is always up to date.

Other examples

How many times have you seen a web platform tutorial where the assets folder

and the place where they are used is far away?

Take this easy file structure:

/assets/images/

- post1-cover.jpg

- post1-thumbnail.jpg

/posts/post1/

- helper.js

- index.jsx

/specs/

- helper.spec.jsThis structure can be familiar to you, but it suffers from DCL. If for some

reason the post1 is no longer needed and it disappears, it is really

probable that the helper.spec.js file will be removed after a failing test but

those assets related to post1 will be forgotten forever.

Check this other example:

components/

List/

index.jsx (has a dependency with ListItem)

ListItem/

index.jsx

stories/

List.story.jsxAlthough this file organization seems inoffensive, it suffers from DCL too. If

the List component disappears, maybe the List.story.jsx will fail as a

side-effect but nobody will alert you that ListItem needs to

be removed too.

How to detect it?

This principle shows up like references to parent components or external resources, but sometimes it is harder to detect it.

The rule of thumbs in all cases is to answer yourself the question:

If I remove this component or piece of code from my code base, will I create leftovers?

With this question, you imagine yourself in the future removing this shiny new code and seeing all the unused pieces in your source code. Answering this question at this point helps you to know all the dependencies this code has.

Better approach

To fix this organization problem, the best approach is to encapsulate better all the dependencies. In the case of file structures try to avoid having dependencies to parent components if a dependency is only used once and move them as child components. All those dependencies can start to use relative paths.

Following the previous example, this would be a much better organization:

/components/

List/

ListItem/

index.jsx

index.jsx

index.story.jsxThis new approach has much better encapsulation and a clear set of dependencies. One direct benefit of this is that it lets you move this component to others around without breaking it.

In some cases, like the translations example, you will need some extra step in your toolchain to resolve those dependencies of your views. In the case of the assets one, you will need your builder (Ex. Webpack) to have support to resolve them.

Conclusion

We just reviewed a few examples of the don’t create leftovers principle. Understanding the consequences in terms of maintainability, you will be able to create and organize your components in a better way that will let you maintain your code base in a healthier way in the long term.

You don’t need to take this principle as written in stone. There are always exceptions or edge cases, as in DRY principle, we don’t have to fall on the wrong abstraction as Sandi Metz mentioned. You have to use it and keep it in mind when you structure your components, views, assets or whatever piece in your project.

I hope this post helps you to spot this pattern sooner rather than later to keep the maintainability of your project under control.

Happy hacking!